Nicolas Poignon and Marcell Feldberg

"We succeeded in something which is very rarely successful—simultaneously working alongside and with each other"

Interview with artist Nicolas Poignon (NP) and poet Marcell Feldberg (MF) was conducted by Emanuel von Baeyer (EvB).

(German translation by Edward Buxton)

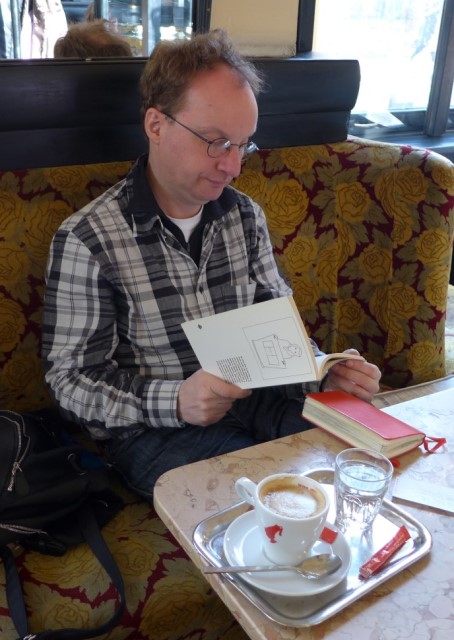

EvB: Rather than asking a question, I

think I’ll begin this interview by telling our readers how I met you both. They

were different routes, of course, but they led to the same point. Marcell, I

first met you at the European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht. I noticed you at my

stand: you stood in front of a small pastel work, examined it intently, viewed

it up close and from a distance. And then I noticed that you had a little

notebook in your hand which you were writing in. I came up to you, we spoke,

and you told me what you do. ‘Picture descriptions?’ I asked, to which you

responded, ‘No, these aren’t painting descriptions.’ How many volumes are there

now? How many volumes of your ‘non-painting descriptions’?

MF: There are now three published volumes

of ‘Archiv der Bilder’ (‘An archive of paintings’). A fourth is in progress.

EvB: And how many texts in each volume?

MF: About a hundred texts per volume.

Some have more, some fewer.

EvB: Right, so that’s about 400 texts on

fine art: about 400 thoughts on a painting, on different paintings, on

different types of painting.

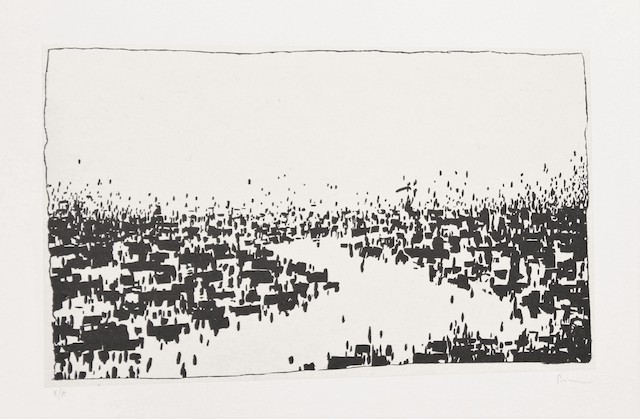

I wanted to

say, too, how I met Nicolas. It was your work that made you stand out for me,

in particular the linocuts. What fascinated me was your technique, and not only

because this technique is seldom used in comparison to other print techniques.

In fact, of the techniques available to them, artists use linocut the least, as

far more often they prefer etching, woodcut and lithography. Then suddenly I

see an artist who creates masterpieces through linocut—not by dint of the

technique itself, but rather the motif, or the structure of the piece. And what

fascinated me here was the relative clarity of the motif, one or two motifs.

Cityscapes, buildings, landscapes—totally classic, scenes we’re all familiar

with. And suddenly you see something rather playful. Raindrops, snow, wind

feature in the depiction. So, we have these two different structures, the

construction of the motif besides the playful. For me, this is all to do with

storytelling. In hindsight, it might have been that my associating your artwork

with poetry inspired this project, albeit subconsciously. Decisions like these

come from the gut.

So, I decided that you should look at each other’s work with an open mind. Marcell, how was it meeting a new colleague, as it were? How did you go about things?

MF: I found a picture of Nicolas at your stand at TEFAF, Emanuel. The picture reminded of the painter Karl Walser, brother of Robert Walser, who disappeared in the snow. That was the first point of contact, so to speak, when you said, ‘You’re the only one to have made that connection’. So I wrote a piece in which I talked about this experience, and then you had the idea of putting me in contact with Nicolas. We got in touch, corresponding by traditional snail mail, to simply get a feel of what one or the other of us was writing, or painting, or setting in linocut. And what I found great was that, as different as we both are, and as different as our working approaches may be, correspondence between us quickly gained pace. We noticed pretty quickly that we had a strong rapport despite all our differences: exactly what you were talking about, really, with the idea of a poetic connection. Depictions of city and countryside are of course something that continues to fascinate me: the dichotomy of being close to the city, but at the same time being in the countryside. And it was this dichotomy which fuelled our correspondence, both literally in terms of our exchanging letters, but also internally in terms of the rapport we built.

NP: I had already bought and read two of

Marcell Feldberg’s books—which wasn’t without its challenges of course, given

that they’re in German, which isn’t my native language. And to begin with I

didn’t understand a thing. But gradually I began to understand parts, and I

liked the style a lot. They’re like diaries—topographical descriptions of

landscapes and walks which I liked very much. And suddenly I had this idea of

pictures, of doing a project together, and an idea that came to me straight away

was the theme of light. I don’t know why, but something bright, something

light. The concept of light is totally foreign to me. My work is dark for the

most part. I mostly work at night. I was working with the night and Marcell’s

descriptions, and I saw something bright, something light, something

spontaneous. And that was a perfect impression for my artwork.

EvB: So that was the first association

between the two of you—an association which hasn’t changed your own work as

such, but rather has been a means of combining it. In almost all cases it is

easier to portray darkness in linocut; light is still a challenge for your

medium.

Of course,

the project was all quite open and gave you both plenty of freedom. At the same

time, it wasn’t meant to be solely illustrative—it was meant to be a two-way

collaboration, working for and alongside each other. Marcel, how did you find

it?

MF: Yes, it was exactly that which I

found so enjoyable. As we’ve said, Nicolas had these particular approaches

which I saw in his artwork—whether cityscapes or landscapes. And what I really

liked about our correspondence was that we always stayed independent to a

degree. It became clear early on that we were working alongside each other—but

only in correspondence. I would get excited about drafts that he sent me, and

then I would reply with drafts or ideas of my own, almost on impulse. And that,

I think, is what became the secret of our project. I think we succeeded in something

which is very rarely successful—simultaneously working alongside and with

each other. That’s what our correspondence meant for me. For me, it doesn’t

have to mean always thinking alike, but rather finding that unity in working

alongside each other.

EvB: Nicolas, is that something you’d also

reiterate, or is there something you would add?

NP: Yes, working with a ‘poet’ is nothing

new for me. I read a lot and am comfortable working with texts. I also often

get ideas or inspiration from texts. I found it interesting working with Marcell

because his work isn’t just illustrative as such. It suited me very well to be

a bit freer.

EvB: Are we now seeing in your artwork how

the formality of a static building morphs into something else?

NP: Naturally when I’m reading something,

I don’t simply want to illustrate the word ‘building’ or ‘snow’ as soon as I come

across it. I don’t have a direct association with snow which lends itself to

representation in painted or other form. It is and stays snow for me. I don’t

simply want to illustrate the snow or the building.

EvB: So, the project is now finished. It’s

presented as a portfolio, with texts to accompany each piece of work, side by

side. We gave the layout a lot of thought, didn’t we?

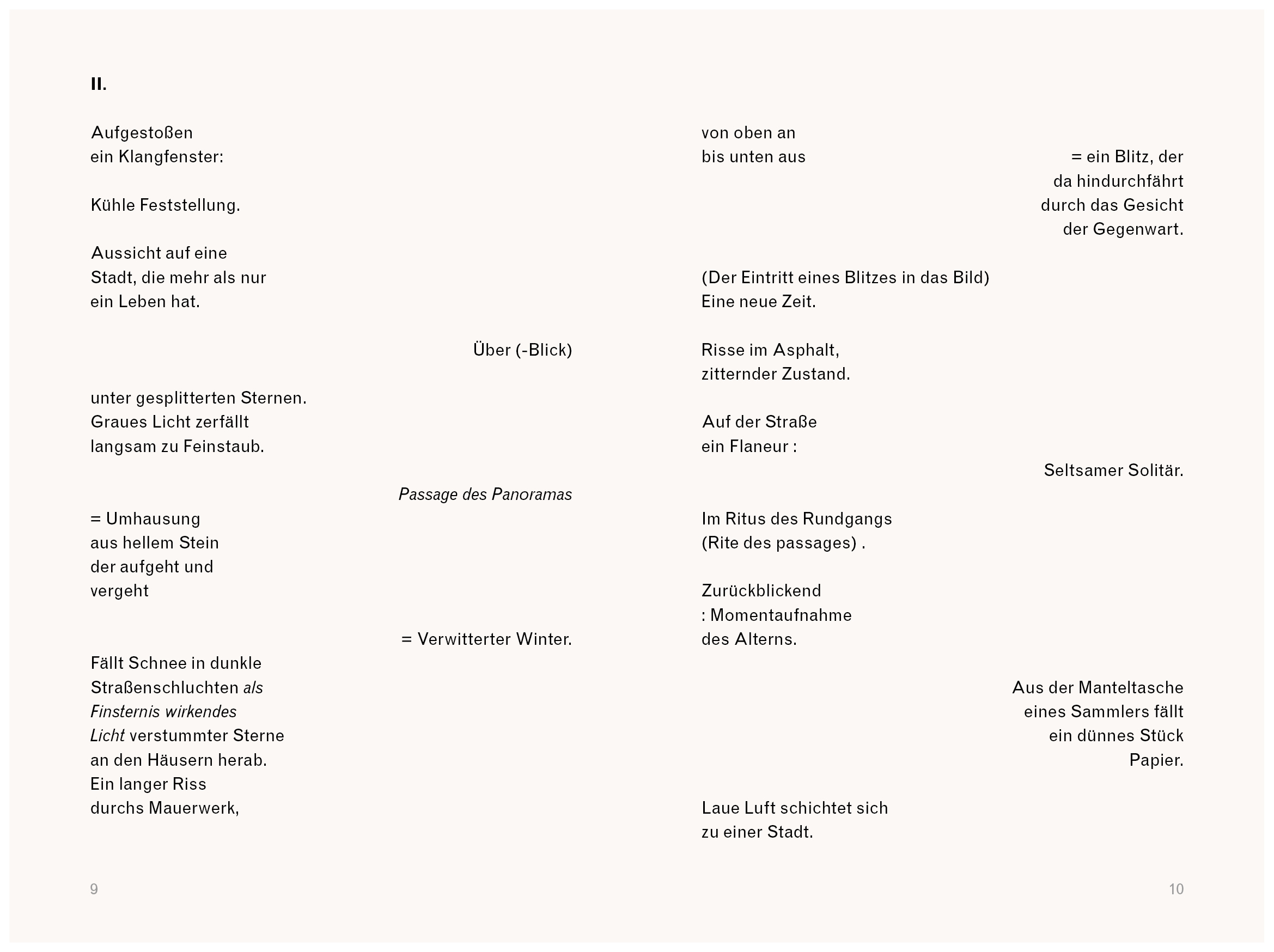

MF: You can see on the pages of text that

the lines, words, thoughts are laid out in a random, scattered way like the

title, ‘Ephemeriden’, which is a mishmash of sorts: on the one hand individual

stars, on the other whole constellations. And when I then look for that in

Nicolas’ works, I see first how the scattered pieces are drawn together into one

cohesive picture—how for the viewer the disparate becomes the whole.

NP: For me a book remains a book, and the

same goes for a portfolio. You leaf through the pages and there you have the

text, there the picture. You can’t change that. And so you begin reading the

text, and gradually take in the picture. I love the concept of that. That’s how

a book should be for me. It’s wonderful. Marcell has his own technique and

that’s also wonderful. I wanted to know how he works. Is it like with

sketching?

MF: So, to begin with I just had the

impressions that I had gleamed from the first picture I bought, and then from

the following picture. The first was a landscape; the second was a view of a

building. When I was then clear that I was going to do something with it and

spend time on it, I got a notebook and kept it with me. And then I began to

collect things—ideas, sentences, single words, newspaper cuttings—which I then

made a careful note of or glued into my notebook. And then I began to organise

texts or lines of texts, and thus came about the notebook that you mentioned

just now, Emanuel—the red notebook that I take wherever I go. During my time as

an organist, I heard the gospel read many a time, and sometimes a line would resonate

with me in such a way that I’d grab my notebook and make a note of it. “He who

lives in the country shall not go into the city”—this line was so striking for

me that it just had to go in. And these would then make their way into the

other sketchbook, which grew and grew over time. In other words, it really was

from these small, disparate collection pieces—these disparate, ephemeral pieces—that

I built the whole thing. That’s how I operate. So it’s a collage really, but a

collage always strongly focused on the object, condensed down in this notebook.

And at some point I ended up at a kind of sequence of texts.

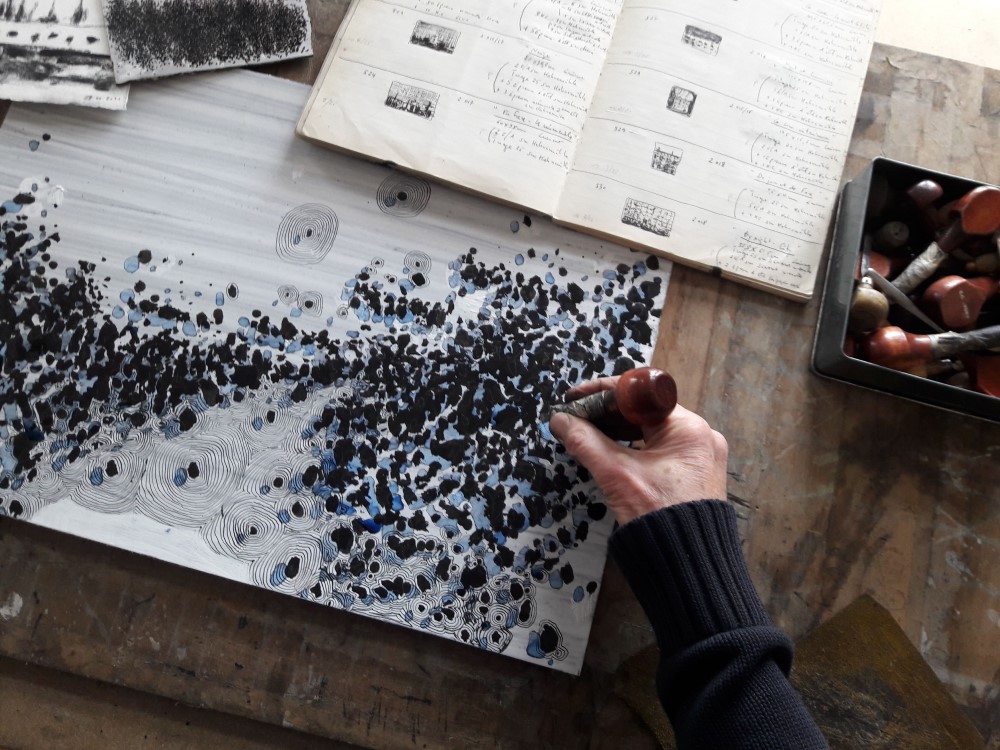

EvB: That’s very true! How do you work,

Nicolas? What techniques do you use?

NP: I do a lot of drawings inspired by

nature; I do a lot of sketches, and even more drawings. And when I have plenty

of drawings, I get the idea of combining them into some larger picture. Only

then do I start making small sketches for the linoleum, and if I like it I enlarge

it before transferring. And the project with Marcell was exactly the same. I did

a lot of sketches and drawings inspired by nature, like keeping a diary. In

some ways, Marcell and I work alike.