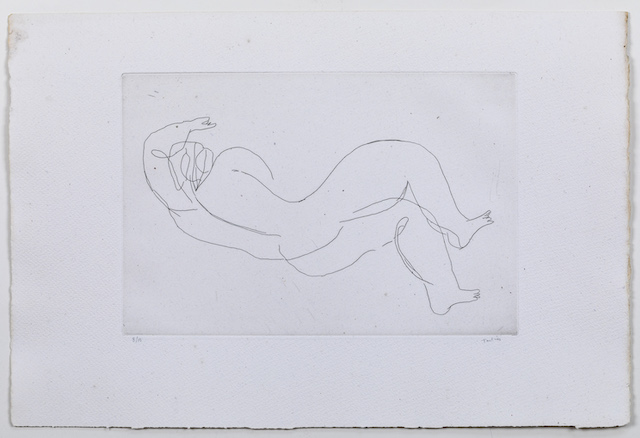

Nu couché III 1944

Jean Fautrier

* 1898 in Paris † 1964 in Chatenay-Malabry

Etching. Size of sheet: 38 x 57 cm.

Signed and numbered 8/10 on Auvergne. Edition Couturier.

Literature: Mason, 1986, ill.141, p.63;

Engelberts 1944/4.

£1,200.-

Born in Paris, Jean Fautrier first trained in London at the Royal Academy School of Arts and the prestigious Slade School where he studied under Walter Sickert, who opened the young artist’s eyes and mind to the likes of Turner. 1914 brought the Great War to Europe and undoubtable personal upheaval. In 1917 Jean would enlist as an ambulance driver “to help bring an end to this war.” The 1918 Armistice signalled the battle’s end, however, two years on and the inevitable symptoms of war moved Fautrier to seek convalescence in the mountainous region of Tyrol near Innsbruck. This period ushered in a return to the brush and palette where he began to produce expressive figures, portraits and still-lives. After recuperation and a short stint in Antwerp, Jean adopted life in Paris, settling in Montmartre in 1922 and in Montparnasse the following year (fig. 1).

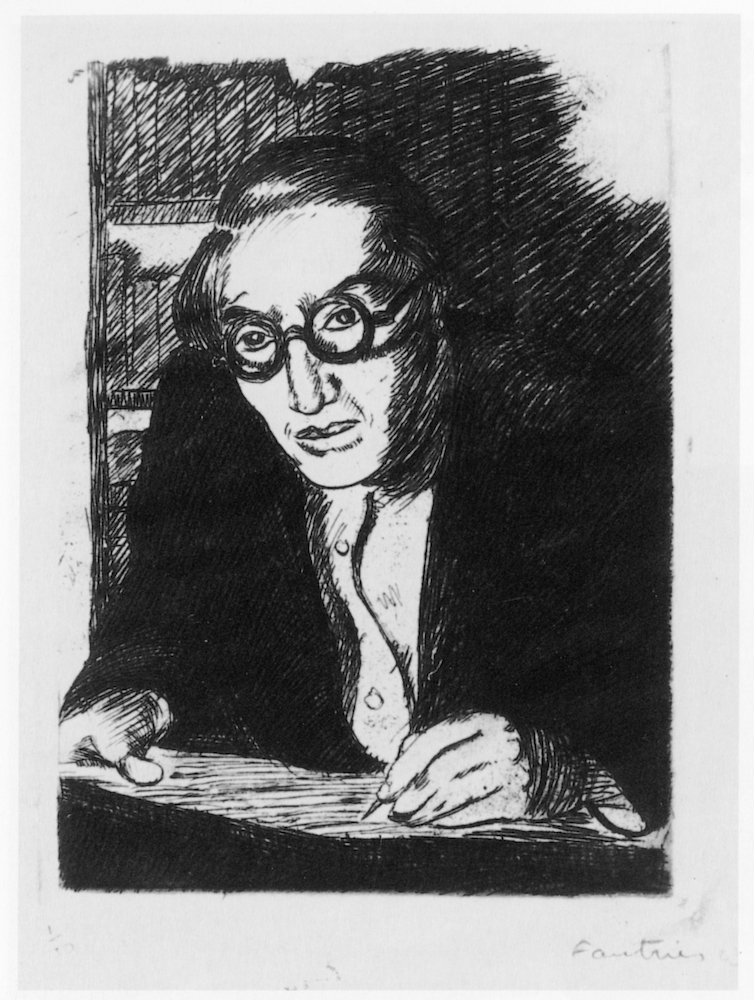

Fig. 1 Jean Fautrier, Self-portrait, 1923. Etching. 12.5 x 9 cm.

There he experimented with colour and monochrome themes, working on etchings, woodcuts and drawings. In the early 1920s his work began to gain public recognition through exhibiting at the Salon d’Autonne as well as remuneration through sales to would be friend Jeanne Castel, whom he met at Galerie Fabre. In 1924 Fautrier had his first solo exhibition at Galerie Visconti, Paris. The following year Castel introduced him to the dealer Paul Guillaume during a trip to the south of France, its resplendent natural beauty clearly of inspiration to the artist. Upon his return to the Alps of Tyrol in 1926, Fautrier revelled in the majesty and power of the mountain lakes and surrounding alpine geology. Prints such as Les cinq arbres and Green trees date to this time and show him exploring those natural subjects that would recur in his work of the 1940s and ‘50s (fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Jean Fautrier, Paysage, 1955. Oil on paper mounted on linen. 58 x 72 cm. Private collection.

The more subdued paintings of his période noir (1926-27) would be exhibited alongside pieces by Modigliani, Kisling and Chaim Soutine by dealer Leopold Zborowski. In 1927 Guillaume paid him a salary to produce a solo show at Galerie Bernheim, this year however would see financial crisis hit. Having remained in Paris until 1934, Fautrier decided to find his way in various vocations in the Alps until 1939 as war broke out. After leaving the Alps for Aix, Marseille, and Bordeaux he eventually moved back to Paris to stay with Jeanne Castel and later Therese Malvaldi. With a studio at his disposal he resumed work and participated in the Salon circuit once again, and in 1942 had a solo show at Galerie Alfred Poyet. To this period date several landscape and still-life prints such as Petit paysage vert et violet and Petit paysage sombre, representative of his almost calligraphic handling of human figures and natural shapes.

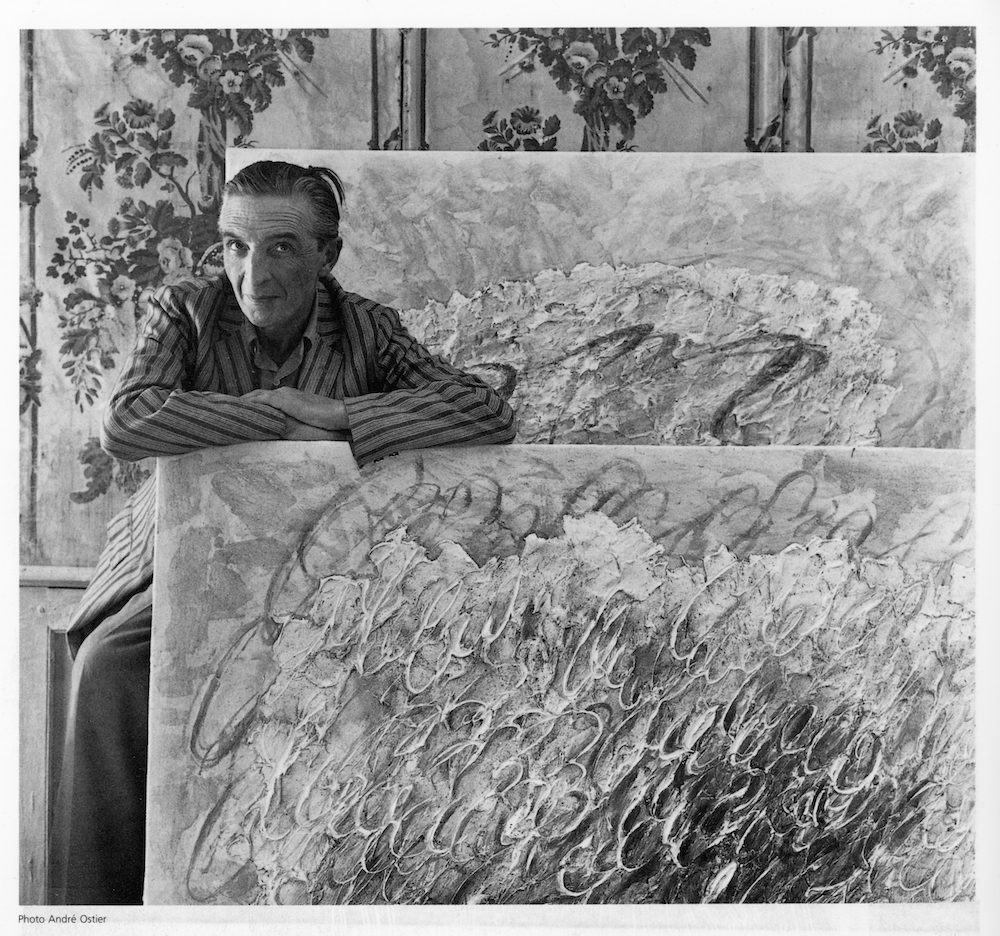

Paris at this time was under the control of the invading forces and having developed close ties with major intellectual figures of the Resistance in 1943 Fautrier was arrested by the Gestapo and released thanks to the intervention of sculptor Arno Breker. Having thus fled Paris, the artist found refuge at the clinic of Châtenay-Malabry (Hauts-sur-Seine), south of the city (fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Fautrier in Chatenay-Malabry

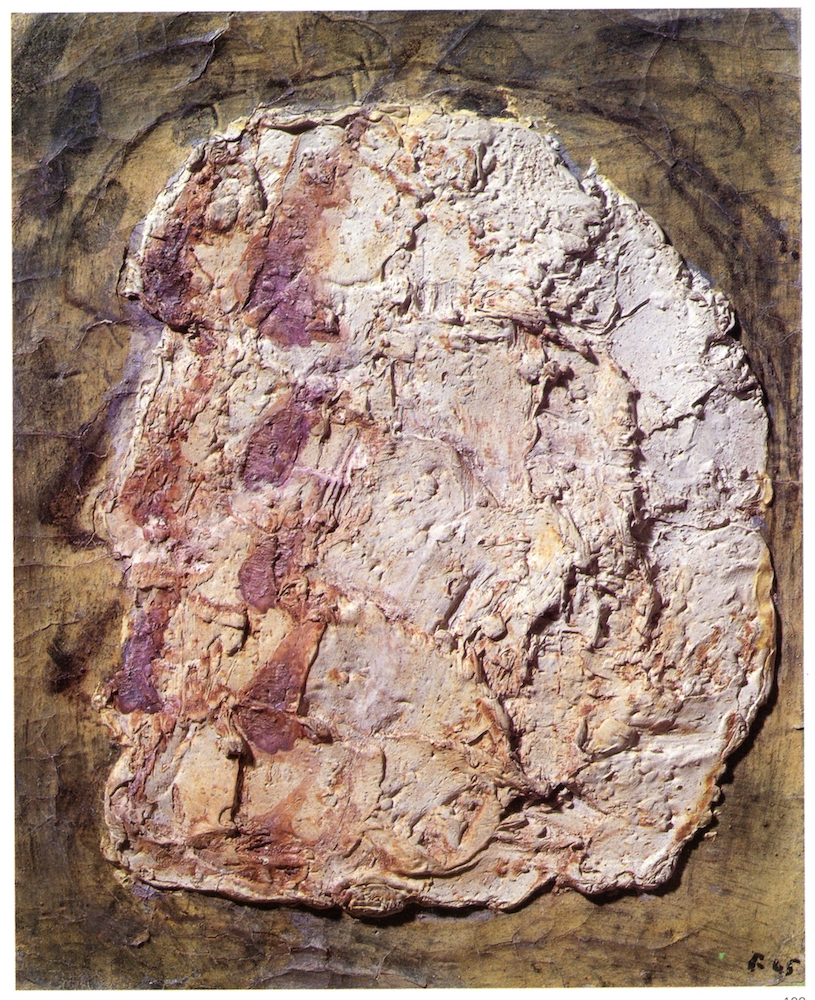

There he began work on the project of the Otages, or Hostages, a series of paintings of anonymous figures created in response to the brutality of war. This body of work engaged the artist across different media and his prints he explored the same haunting subjects that populated his paintings. Indeed, his original approach to printmaking, with its emphasis on layering and scratching, may have informed the development of his distinctive painting technique, normally mixed media on paper mounted on linen. The hostage’s profile in Tete d’otage no. 4 is rendered with a thick impasto, its surface rough, scored and cracked (fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Jean Fautrier, Tete d'otage no. 4, 1944. 46 x 55 cm. Private collection.

If the anonymous subject may only be redolent of imprisonment and isolation, it is with his handling of paint and matter that Fautrier exposed the brutalization of the body. The composition is almost identical in Tete d’otage no. 22 (fig. 5) and in the prints entitled L’otage aux mains I and II.

Fig. 5 Jean Fautrier, Tete d'otage no. 22, 1944. 27 x 22 cm. Private collection

Here, the colour range and textural quality of aquatint parallel the play with thick paint layers. In another print, Otages fond noir, 1946, he overlapped the outlined profiles of four hostage heads, the colour scheme pared down to black and white. He would revisit the same war-related themes in other works such as the print Les Fusillés. First exhibited in 1945 at René Drouin’s gallery and harshly criticised at the time, the Otages series would ensure his long-lasting fame. Up until 1943 Fautrier also made forays into sculpture, using the medium to extend his investigation of his favoured subjects, namely the nude and the isolated, tragic head, thus furthering the continuous dialogue and crossover between his paintings, drawings and prints.

Following the war Fautrier’s financial situation was challenging, until writer Andre Malraux (later French Minister of Culture) offered him the position of graphics editor of art editions in the Gallimard publishing house. Seeking new outlets for his free innovation in printmaking, together with his wife Jeanine Aeply, a fellow artist and writer, he developed his Original Multiples, a mixture of printmaking and painting. By the mid-fifties he returned to painting in oil and would eventually exhibit internationally at prominent shows such as the 1959 Documenta II in Kassel. As guest of honour at the 1960 Venice Biennale he was awarded the Grand Prix for painting and devoted a large solo exhibition in the Italian pavilion. Amongst his last works are the large prints Construction and Paysage in which he exploited the luminosity of aquatint. Fautrier’s printed oeuvre, comprising just over 300 works, shows him progressively blur the boundaries between figuration and abstraction and between the linear and the painterly, in search of a personal language.