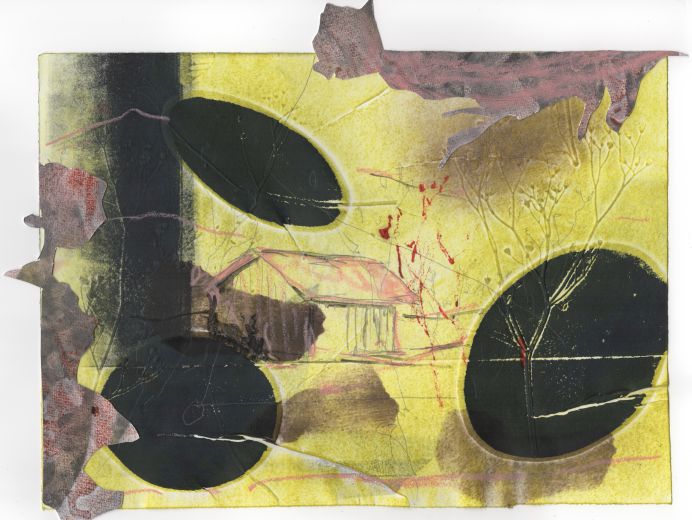

Realms of Living. 2019/2020.

Clemens Büntig

* 1968 in San Francisco

Monotype, collage overworked with oil. Size of plate: 32 x 38 cm. Size of sheet: 32 x 38 cm.

Unique. Signed and dated.

€ 580.-

Line, Space and the Indefinite – on the nature of Clemens Büntig’s pictures

By Dr. Andreas Strobl

A man walking across the meadows – picking a flower here and there, gathering twigs, taking them home. The open countryside is of great importance to him. It represents a space that also liberates us humans, a space where the big and the small can be found close together.

This is how I imagine Clemens Büntig, the wanderer and gatherer, going out to capture booty, not glancing at what lies far off but close up. The artist then sits in his studio, holding what he has collected in one hand and drawing it with the other one. He carefully observes patterns and deviations, the individual flower, the singular panicle, its outline and branchings. While observing, the other hand draws what is seen. The eye mediates between both hands and structures emerge on the paper or even immediately on the printing plate, structures that gradually transform into a picture.

Today it is rather unusual that an artist follows a concrete object and, in these days of digital storing, in the blink of an eye, such close observation, the exact study, is the artist’s main artistic technique. It is unusual as it is rooted in the old traditions of observation, control and especially practice. In fact it is the practice itself that turns this technique into something natural.

In doing so, Clemens Büntig’s interest lies neither in a particular panicle nor in giving a generally valid description of a plant in a botanical sense. Instead his interest lies in the forms and organic bodies that come to life on the surface and so become a unique signature. By contemplating the twig held in the one hand, memories of many other previously looked at twigs well up. A picture is created by concentrating on the concrete object that, despite all its resemblances to the object’s true nature, bears the artist’s individual signature.

A crucial aspect of this signature is the fact that the artist prefers a complex creation process, which proves to be full of obstacles, by opting for the technique of etching, a technique that requires many individual steps. He takes all these steps himself – from sketching on the metal plate, to choosing the kind of etching technique and the colours and paper, to finally the printing itself. This needs to be mentioned as many artists tend to seek help from professional printers with this complex technique to avoid having to understand and tackle the specific aspects on a deeper level. Clemens Büntig, however, is such a professional printer himself, who also imparts his expertise to other artists. When doing so he has to meet the needs of his clients and stick to their aims meticulously. He does not print his own graphics, however, with the aim in mind of creating a perfect edition. It is rather the playing about with the technical options that drives forward the working process on a picture. In this process, the artist enjoys being surprised himself by the endless possibilities offered by the various techniques - gravure printing, aquatint, open deep etching and direct etching or dry point – to name but a few.

All these options are strongly intensified by the use of colour and by how Büntig almost always applies it.

The way his work has been described so far may lead to the impression it consists of linear drawings in black and white.

In the etching process, however, the colour takes on a role of its own. It does not describe the object but intensifies the three dimensionality of perception. It often makes the object shine, mostly in front of a neutral background, and this shining is hard to explain. It stems from within, which also increases the tension along the contour lines.

Painting is, as is linear sketching, of equal importance to Büntig’s art. Not only does colour add an effect of painting to the sketch, but for his work it has also recently gained importance in the examination of blurring. The precise outline of a singular object has retreated into the background and been replaced by experimenting with flowing colours. Puddles of heavily diluted ink are spread on rag paper, turning wavy, and are divided and structured by the line of the drawing, which in return mingles with the puddles.

For this game between drawing, ink and water the artist has found inspiration in the shadow play of trees and leaves outdoors on the ground, which he observed by putting cardboard on the ground and taking photographs of the shadows. In their shadow form the objects lose precision, but not their three dimensionality entirely.

When not viewed directly, their contours change and other intensities of colour emerge.

Just as in observing the precise contour, in the attempt to paint the imprecise there lies the danger of succumbing to the effect of the colours flowing into each other. Also in drawing precise lines where there are really flowing shapes lies the danger of eventually creating something only decorative.

By the way the forms are placed on paper and by creating a coarse effect through flowing and dropping ink, the artist successfully resists the draw of the decorative. This blur of flowing shapes and lines is even destructive to a certain extent as the picture created may not be easy to grasp for the viewer, who at the same time has the impression that more was recognizable before.

His work with plants and natural phenomena leave little space for aesthetic ruptures. A flower and the unusual form of a twig easily turn into something special, which is full of variations and exhilarating for the viewer and hence seems beautiful.

The artist has often been told that his pictures are beautiful, even “too beautiful”. If he painted non-figurative colorfields, he would hardly have to justify himself. But by portraying the concrete the beauty of the result is forced to explain itself.

In the course of the 20th century this category of art has fallen so much into disrepute that “beauty" makes it almost impossible to be regarded as “good" art.

Ruptures and resistance have become the aesthetic methods of a modern age that believes it needs to oppose all that is beautiful.

Against this view, Clemens Büntig’s pictures make a succinct statement: That beauty in the sense of exhilaration and the well shaped must today again or still be seen as detached from the obligations of the anti-tradition of the modern age.

As the motto says: “We won’t allow beauty to be banned."