Francis Bernard

From Experimental Photography to Advertisement

Though perhaps not garnering the name recognition some of his contemporaries – Charles Loupot, Cassandre, or Jean Carlu, say – the schematised posters, billboards, and advertisements of Francis Bernard (1900 Marseilles – 1979 Bandol) are just as strikingly effective. Having Studied at Ecoles de Beaux-Arts in Marseilles and Paris and under Ernest Laurent, Bernard channelled his artistic talent into advertising from 1925. Bernard, simultaneously a progressive leftist and a commercial artist, sublimated this dissonance into a spirit of systematic artistic experimentation. Recent critical evaluations have begun to cast him as ‘totalement innover’ for his time, especially in his use of photography in collage with schematised illustration.(1)

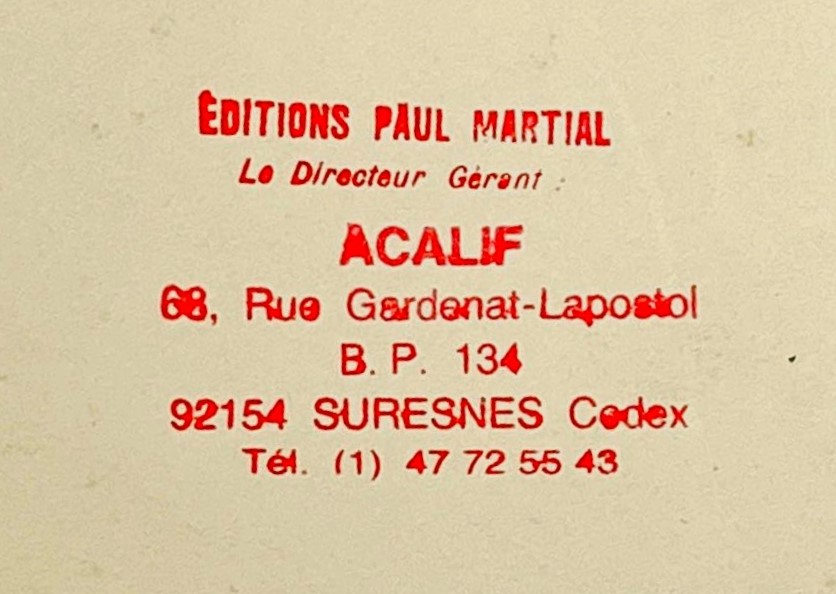

This collection of twenty-five

gelatin silver prints is from the archive of the Parisian advertising agency Éditions

Paul Martial for whom Bernard designed from 1927. Almost all of the prints

in this collection feature the agency’s stamp on verso (see left). These

archival photographs provide a rare glimpse at both the products and process of

Bernard’s craft. Posters in their final states are placed alongside works ‘under

construction’ – either drafts for constituent elements of an advertisement

(e.g., GEP Man), or mock-ups or presentation pieces (e.g., Brasserie

Bar Mazagran). The posters thus photographed exist in an ambivalent state: eventually

intended for mass public display, yet fringed with glimpses of the artist’s

studio and ultimately stored in a private archive; at once in construction and

simultaneously solidified and complete by the sign-making of photography.

Bernard was starkly aware of the solidifying capacity of photography. The schematising, minimalist style of early-twentieth century French commercial poster art sought to simplify the complexity and triviality of modernity. Conversely, Bernard found in photography the elements of precision and surprise. Pierre Andrin, who interviewed Bernard in a 1930 edition of L’Affiche, termed this effect l’incorruptible fidélité de l’objectif’.(2) The quibble of ‘l’objectif’ is subtly illuminating – contained inside the French conception of the camera lens was the capacity for total objective signification. Where the vogue in commercial poster art was to use simplification to land on the essence of a figure, Bernard saw the potential for photography thriftily to ‘meublera le symbole à l’aide d’un apport concret’.(3)

Bernard’s first poster to employ the technique of photography in collage was for l’Exposition de l’Habitation in 1929, the photographic proof of which is exhibited in this collection. Bernard’s superimposition of steel plating around the silhouette of the house comprises the literal and figurative, advertising and aesthetic framework of the poster. The schematised drawing, which Bernard views as purely ‘symbolique’ is placed in collage – and thus simultaneously contrasted and supported – by the purely ‘matériel’ photograph.(4) In this context, Bernard sees schematised illustration appropriating and imbuing itself with photography’s materiality and perceived objectivity. This, in a way, solidifies the dubious referentiality of the minimalist illustration as sign.

read more

Bernard, Francis

Huile d'Olive de Tunisie

Silver gelatin print.

Size of sheet: 24.4 x 19 cm

Bernard, Francis

Exposition de l'Habitation 1929

Silver gelatin print.

Size of sheet: 23.9 x 17.9 cm

Bernard, Francis

CAFD Douvres-Calais

Silver gelatin print.

Size of sheet: 23.5 x 19 cm

Bernard, Francis

Bière Remoise

Silver gelatin print.

Size of sheet: 23.9 x 17.9 cm

Bernard, Francis

Three Men

Silver gelatin print.

Size of sheet: 23.8 x 17.9 cm

Bernard, Francis

Tridigestine Dalloz

Silver gelatin print.

Size of sheet: 23.9 x 17.9 cm

Bernard, Francis

Anti-Douleur Compral

Silver gelatin print.

Size of sheet: 23.7 x 17.7 cm

Bernard, Francis

Wine Drinker

Silver gelatin print.

Size of sheet: 23.9 x 17.9 cm

Accordingly, this interplay proliferates in our collection, given that Bernard’s works were themselves photographed, and that it is in this form we encounter them. Photographs of disembodied elements (eg., Wine Drinker or GEP Man) are not trial proofs, but become solidified into artworks in themselves. It is possible that Bernard used these photographed elements in collage later. For example, the travel slip and GEP Man in Bon Produits Bon Voyage have a surprisingly heightened precision when compared to the poster’s other elements. Did Bernard photograph smaller detailed works then translate them as photographs in finished posters? Indeed, the photographic archive of Éditions Paul Martial was essentially a font for artists from which to draw intermediary products and materials, later translated into posters and advertisements. This aspect of the archive has been comprehensively explored in the exhibition ‘Paul-Martial’s Welt der Gewöhnlichen Dinge’ at the Kunstmuseum Basel.

Even when the posters in this collection follow more conventional schematic and minimalist trends, when photographed and bordered by the materials of the artist’s studio (as many are), the process of juxtaposition and solidification plays out again. Just as metal plates fill up the house’s silhouette from outside, here the cork board, floor tiles, pins and cords which surround the poster-in-production populate it with the real world, material applicability which the complete poster will need as advertisement.

The fringe materiality of the photograph binds together the elements of collage into one contiguous whole with the world around it, rehearsing the relationship between the simplified poster and the feverishly triviality of the modern world, testing out not only form or composition, but its capability of being propagandistically effective.

1. 'totally innovative’, as Anne-Céline Callens terms him in ‘Francis Bernard et les premiers pas de la photographie dans l’affiche publicitaire en France’, Focales, vol. VII (2023), p. 16

2. 'the incorruptible fidelity of the lens/objectif’, Pierre Andrin ‘Francis Bernard, artiste-affichiste’, L’Affiche et les arts de la publicité, no 62, (February 1930), p. 240

3. ‘furnish the symbol helpfully with concrete contribution/material’, Andrin, p. 244

4. 'symbolic', 'material', Andrin, p. 241