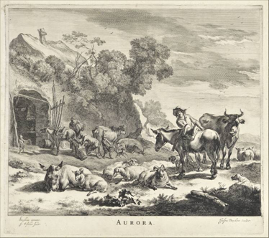

Aurora. 1770 circa

Pietro Giovanni Palmieri

* 1737 in Turin † 1804 in Turin

Traces of graphite, pen and black ink, grey wash after Nicolaes Berchem (1620 Haarlem - 1683 Amsterdam). Size of sheet: 30.1 x 36.7 cm.

After Jan Visscher’s etching and aquatint of c. 1660 of the composition by Nicolaes Berchem.

Watermark: Armorial shield surmounted by a crown, with the letters ‘VV’ below.

Literature: Chiara Travisonni, Pietro Giacomo Palmieri, 1737-1804, Florence 2023, pp. 68-69, pl. 7.

Provenance: Private Collection

A glance at this sheet from a short distance could well suggest it is a print, but a closer look reveals it to be a drawing. Such ‘disorientation’ was entirely intentional on the part of the draughtsman. Chiara Travi-sonni recently recognised this as one of the few examples of known works by Pietro Giovanni Palmieri. His father, the great Pietro Giacomo Palmieri (1737-1804), abandoned religious studies to enrol at the Accademia Clementina in Bologna, and ultimately won great fame in Paris for his landscape drawings ‘du plus grand effet’ intended as unique finished works for sale. These were greatly admired by French artists and aristocratic collectors alike. (1) Working from his studio opposite the Louvre he produced landscape drawings in the manner of 17th-century artists active in Italy, from Claude to Dutch Italianate artists like Jan Both, Karel Dujardin and especially Nicolaes Berchem, many of whose prints he owned. (2) Ultimately he worked at the Savoy court; first under the protection of Prince Luigi Vittorio di Carignano (1721-1778), who appointed him ‘Primo disegnatore’, and then for King Vittorio Amedeo III (1726-1796) as adviser to the royal collection of prints and drawings. (3) In 1802 he was nominated Professore di disegno at the city’s Academy.

His son, Pietro Giovanni trained at the Accademia Albertina, Turin, where he studied drawing under Laurent Pécheux (1729-1821) and engraving under Carlo Antonio Porporati (1741-1816). Impressive teachers, since Pécheux had worked in the studios of Charles-Joseph Natoire, Jean-Baptiste Pillement and Anton Raphael Mengs, and in Rome befriended Pompeo Batoni. Porporati, a member of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, Paris, was Professore del disegno at the Turin Academy. The young Pietro Giovanni shared his father’s passion for landscape and learnt much from him about media and tech-nique. He successfully assimilated his father’s style and ability to replicate in ink and wash the wide range of textures and atmospheric effects created by a skilled engraver. Among the traits that distinguish son from father are Pietro Giovanni’s occasional use of miniscule penlines and cross-hatching, as seen in areas of the present drawing. (4)

This drawing is anything but a straight copy or facsimile of Jan Visscher’s etching and aquatint of Aurora, the first in the series of pastoral compositions representing the Times of Day designed by Berchem (Fig. 1), the much revered Italianate landscape painter of the Dutch Golden Age. (5)

Berchem’s typically animated bucolic scene is set against an escarpment. Above is a farmhouse, and below a forge cut into the rockface where a blacksmith, watched by a mother and child, attempts to shoe a reluctantly braying donkey. In the midst of animals at rest, yapping dogs and bleating sheep, a peasant saddles his donkey. Next to him is a glaring bull, and by the forge a child in a world of his own plays with a spinning top.

Berchem’s typically animated bucolic scene is set against an escarpment. Above is a farmhouse, and below a forge cut into the rockface where a blacksmith, watched by a mother and child, attempts to shoe a reluctantly braying donkey. In the midst of animals at rest, yapping dogs and bleating sheep, a peasant saddles his donkey. Next to him is a glaring bull, and by the forge a child in a world of his own plays with a spinning top.

The present drawing is not especially Netherlandish in handling; it has more in common with the drawings and engravings of the great Bolognese draughtsmen of the late 17th century. Close comparison with the print reveals that it is not a tracing. The dimensions differ, resulting in a mis-match in compositional detail when one is laid over the other. (6) Nor is it a straightforward line-by-line copy. Rather than follow the graphic idiosyncrasies of Berchem’s design, Pietro Giovanni worked freehand in ink in his own style over loose graphite underdrawing (Figs 2a-b, 3a-b). Seeking to emulate his father’s ‘virtuoso and effortless penmanship’ (‘uso virtuosistico della penna con disinvoltura’), Pietro Giovanni worked with a sharply cut nib and saturated washes to evoke the effects of etching and aquatint (Figs 4a-b, 5a-b). (7)

Though Berchem was very much in vogue in Paris, awareness of him was slight in Turin at the time Pietro Giovanni’s father moved there. His impact on the court and educated élite of Turin was profound; he inspired connoisseurs to collect drawings and engravings influenced by the Dutch tradition, and was instrumental in introducing Turin to the Parisian vogue for the ‘new technique’ of drawing in imitation of prints. (8) In Turin, as in Paris, such drawings became highly valued on several counts. First for the way a skilled draughtsman, employing a totally different technique to that of printmaking, could replicate the process of etching and aquatint. Second, how by mimicking past masters it was possible to present them in a new light. Third, collectors revelled in the way such ‘optical trickery’ could totally disorientate spec-tators, unsure – at first sight – whether they were looking at a drawing or a print. And fourth, the more knowledgeable connoisseurs could delight in the fact that the drawings were in the grand manner of the previous century, and they could display their knowledge in recognising ‘quotations’ from the works of long-past masters. Such social dynamics and niceties demonstrated the excellence and cultivated taste of collectors. Thus, thanks to Palmieri, what became known as ‘the taste for creating confusion through technique’ – ‘il gusto per lo scambio delle tecniche’ – blurring the boundaries between drawings and en-gravings, migrated from France to Italy. (9) He paved the way for his son to continue the tradition, and though Pietro Giovanni’s career has yet to be studied in full, he appears to have done so to great effect.

Thanks are due to Chiara Travisonni from the Università degli Studi di Parma for confirming the attribution of the present drawing.

Please view the notes in additional information.

Fig. 2a. Pietro Giovanni Palmieri after Berchem, Aurora (detail, left of centre) |

Fig. 2b. Pietro Giovanni Palmieri, Peasant on Horseback (detail). Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada 28153 |

Fig. 3a Pietro Giovanni Palmieri after Berchem, Aurora (detail, right of centre) |

Fig. 3b. Berchem, Aurora (detail) |

Fig. 4a Pietro Giovanni Palmieri after Berchem, Aurora (detail of entrance to the forge) |

Fig. 4b. Berchem, Aurora (detail) |

Fig. 5a. Pietro Giovanni Palmieri after Berchem, Aurora (detail, upper right) |

Fig. 5b. Berchem, Aurora (detail) |

£ 8500.-

NOTES

1 Chiara Travisonni: Pietro Giacomo Palmieri (Bologna, 1737-Torino, 1804), PhD Thesis, Università degli studi di Parma 2013, p. 13; ‘Escursioni virtuosistiche tra tecniche artistiche e fonti figurative: il caso settecentesco di Pietro Giacomo Palmieri’, Ricerche di S/Confine, IV, 2013, pp. 147-69.2 Travisonni 2013 (Escursioni), pp. 158, 164; Vittorio Natale, ‘Pietro Giacomo Palmieri. Bologna 1735-Turin 1804’, in Disegni del XIX secolo della Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna Contemporanea di Torino. Fogli scelti dal Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, ed. Virginia Bertone, 2 vols, Florence 2009, I, pp. 3-9. Al-so Laura De Fanti, ‘Citazioni da Nicholaes Berchem in disegni del Palmieri bolognese’, L’arte nella storia. Contributi di critica e storia dell’arte per Gianni Carlo Sciolla, ed. Valerio Terraioli, Franca Varallo & Laura De Fanti, Milan 2000, p. 347-51.

3 Travisonni 2013 (Escursioni), p. 154.

4 Chiara Travisonni, Pietro Giacomo Palmieri, 1737-1804, Florence 2023, pp. 65-66.

5 F. W. H. Hollstein, Dutch and Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts c. 1450-1700, Amsterdam 1949 onwards, 1-2 (2). The lower margin of the print is inscribed with its title and production details: C Berghem inventor / J. Visscher fecit and the name of the publisher, Justus Danckerts Excudit. The companion pieces represent Meridies, Vesper and Nox.

6 Examples of the print with wide margins and complete lettering preserved in the British Museum (Nn,7.11.1) and the Rijksmuseum (RP-P-OB-47.283) measure 321 x 368 and 328 x 372 mm respectively.

7 ‘… trattati con accuratezza, finiti con somma precisione, e grazia … ben poco può desiderarsi di meglio … tutto tratteggiato a penna che di meglio non aveva a vedersi’. See Travisonni 2013 (Thesis), pp. 11-12, citing Scarabelli-Zunti’s Memorie e documenti di belle arti parmigiane, preserved in manu-script.

8 Travisonni 2013 (Thesis), pp. 66, 151.

9 Travisonni 2013 (Escursioni), pp. 150-52, 157-58.